[Who else has walked here?]

It’s rare to walk the Earth and not be following in the footsteps of others. At our first campsite, we’d sat relaxed and content – when the weather allowed – and imagined the Palawa, Tasmania’s Aboriginal people, doing much the same over tens of thousands of years. The shelter, the water, the hunting, the clear views, would all have made this a wonderful summer place. What stories, songs and dances must they have shared here, and passed on for countless generations?

[A place of contentment]

For the Palawa, European invasion stopped all that, whether though disease, forced eviction, or deliberate killings. Others would now eye off this high country for their own purposes, and they did so quickly. In the 1830s, when G. A. Robinson (the so-called protector of Aboriginals), travelled through the Central Plateau to round up any remaining Aboriginals, he noted that “wild cattle was seen grazing … and several young calves appeared among them”.

So this “empty” Central Plateau became a favoured place on which to summer livestock. It’s estimated that between 1860 and 1920, up to 350,000 sheep and 6,000 cattle were summered up here annually. This is tranhumance on a grander scale than I’d ever imagined. Gradually cattle became more highly favoured than sheep, and by the late 1870s, settlers from the Mersey Valley and surrounding districts had acquired cattle grazing leases on the plateau. They built tracks such as Higgs Track, Warners Track and Dixons Track so they could drive stock up to the high country each summer.

But as we were discovering first hand, the “warmer” months on the plateau can still be harsh, making navigation difficult. Around 1913 a farmer from Meander named Charles Ritter, who had leases in the Walls of Jerusalem area, thought to make a safer all-weather drove route from the top of Higgs Track/Ironstone Hut area to the Walls. It was probably completed by 1918, and became known as Ritters Track. While it was called a track, I had long wondered whether it was ever more than a series of large rock cairns that could be followed even in rough weather. On our fourth day, we were hoping to find out for ourselves.

[An old sketch map by Keith Lancaster, showing Ritters Track]

The night had been exceedingly windy, and none of us had slept much. Jim wasn't feeling great after a poor sleep punctuated by some unwelcome toilet trips in the dark. We’d already decided to adapt our schedule, allowing for another night here at Pencil Pine Tarn, and a short wander today. That meant Jim could stay back and “keep our camp secure”, which he generously volunteered to do. The rest of us would pack lunch and a day pack, and go in search of Ritters Track.

Three years earlier we’d half-heartedly looked for some cairns between here and Long Tarns. That time we’d only had some rough, third-hand notes, and our explorations hadn’t allowed us to say with any certainty that the cairns we found were part of Ritters Track. This time, we had not one but two lots of GPS data indicating the supposed locations of Ritter’s cairns. The only thing against us was the weather, which remained showery and ferociously windy: in short exactly the kind of weather Ritter hoped his track would deal with.

[Tim contemplates the route]

Tim and Larry, our two GPS-bearers, lead the way, at first taking us almost east, seemingly back to where we’d come from. I expressed my surprise, but Tim assured me we’d soon swing south. And once we’d picked up a cairn, we’d start heading more south-west.

Before long one of our navigators signalled us to join him. According to his GPS, we were within 20 metres of one of the cairns. But what were we looking for? A pile of rocks in a landscape made of rocks? And rocks that have been glaciated, ice-shattered, and scattered about willy-nilly over aeons? The five of us wandered about, a little clueless, until someone finally had their eureka moment.

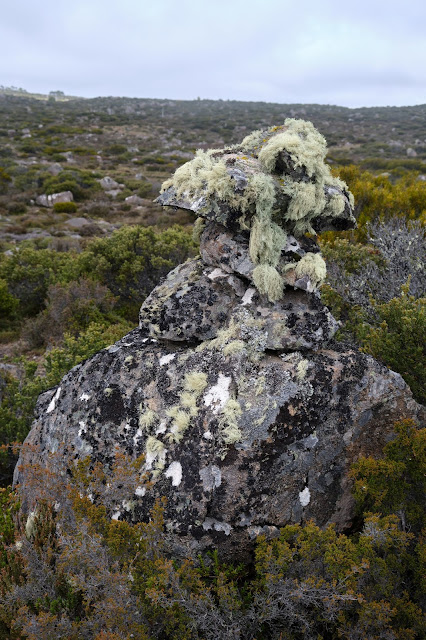

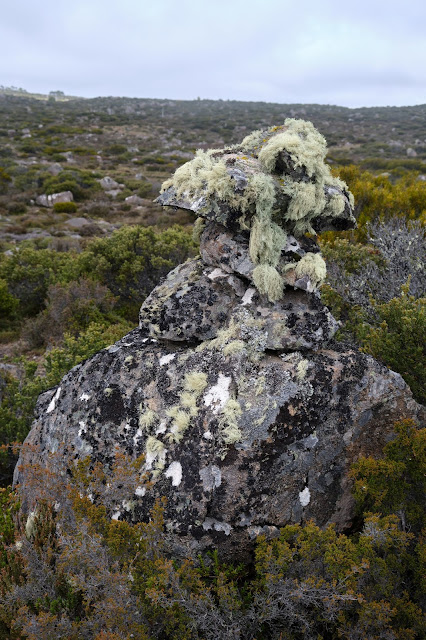

[Surely a Ritters Track cairn?]

We hurried over towards an obviously human creation: four or five rocks piled high atop a large boulder, forming a rough and wonky pyramid. If the cairn’s size wasn’t the clincher, the mop of long, grey/green lichen on the rocks was. This indicated it was no recent or random cairn, but one put here deliberately, and many decades ago.

[Tim and Larry spy out the next cairn]

The next couple of hours saw us slowly following our navigational nerds from cairn to cairn. Sometimes the next cairn was visible from the current one, but at other times we were glad to have the GPS data. This was not the sort of “track” that, once found, you could easily follow. Apparently Ritter didn’t choose a straight-line route towards the Walls of Jerusalem (which today was clear to see ahead of us). Rather he kept to higher, less boggy ground, winding around the plateau on ground over which cattle could more easily move.

[A clear view towards the Walls of Jerusalem]

Another matter sometimes confused us. We found multiple other cairns dotted across the landscape. Some we considered Ritteresque: good copies, but not originals. Others were mere wannabes: poor imitations that lacked size or age, the creation perhaps of bushwalkers or anglers. Our rule of thumb was that a true Ritter cairn would be substantial, vaguely pyramidal, made with care, and bearded with lichen. We came to admire the labour that Charles Ritter, presumably with the help of his fellow drovers, had put into building the many dozens of cairns. The heavy rocks would have taken some effort to move, and the conditions for doing that work would seldom have been ideal.

[Libby inspects another genuine Ritter cairn]

As we walked, we imagined driving cattle through this terrain. How different it would have been to walk or ride here accompanied by the sound of hoofs and mooing; the steam from their breath; the swish of their tails; the slop of the slush beneath their hard hoofs; the smell of dung and drover alike. We could admire, celebrate even, the hard labour of these cattlemen, without wishing that this was still happening. Clearly driving and grazing cattle between here and the central Walls – where the best grazing was found – made a mess, and altered the landscape hugely. The unsustainability of the practice, both environmentally and economically, led to grazing being prohibited above the 3000ft contour (914m) in 1973.

[Tim and Merran at our lunch stop]

While it had been fascinating to follow the footsteps of Ritter, after lunch it was time to complete our off-track loop back to the campsite. We were beginning to wonder how another grey-bearded fixture was doing. We found Jim relaxing in the sun, which had finally made a welcome return. As Tim placed his small solar panel in the same patch of sun as Jim, I remarked that we now had two solar collectors. Then, over a relaxing afternoon tea, we swapped stories of our day. Jim noticed that a couple of us were red in the face, and when we conjectured that a combination of windburn and sunburn might be to blame, he was all the gladder for his rest day.

[Two solar collectors hard at work]

When the shade from the pines started overtaking us, we followed the sun up the hill. It was good to gain a little altitude, to change our perspective, and to feel a windless sun after 48 hours of gales. Eventually we wandered back down to the camp, and we were soon off to our tents. How good it felt to be in that now quiet space, without wind tearing my every thought away.

[A calm Pencil Pine Tarn]

In that calm state, I began to ponder on our walk, and to think about the footsteps we had followed to this point. Whether it was those of the Palawa, those of the cattlemen, or those of the pioneer bushwalkers, the ones who were here before us are now gone. Without feeling at all morbid, I apprehended afresh my own impermanence. None of us – grey-bearded or not – will hang around even as long as Ritter’s cairns. Sooner or later each of us will follow in the footsteps of those who are gone.

It was in a time of pandemic, nearly 400 years ago, that poet John Donne reflected so powerfully on this.

No man is an island,

entire of itself,

every man is a piece of the continent,

a part of the main; …

any man's death diminishes me,

because I am involved in mankind,

And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls;

It tolls for thee.