In 1678, when John

Bunyan was choosing a landscape in which the hero of The Pilgrim’s Progress might experience despair, he looked no

further than a bog.

They drew nigh to a very miry

slough that was in the midst of the plain, and they, being heedless, did both

fall suddenly into the bog. The name of the slough was Despond.

|

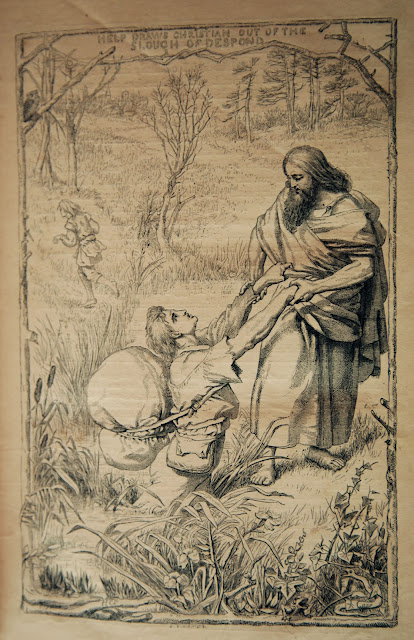

[In the slough of despond. (Illustration by H.C. Selous from an 1870s edition of The Pilgrim's Progress] |

Since Bunyan’s time

much has changed in the world. But whether you call it slough, bog, mire,

marsh, mud, swamp or sludge, there are still few who’d name such a place their

favourite. And in the case of our mate Jim, there’s certainly no trace of

Eeyore*, which is probably why Tim and I haven’t worded him up on our dirty

little secret. The truth is we’re

determined to visit some bogs in the

high alpine zone of Tasmania’s Mt Field National Park.

The three of us

have spent our first night in a private hut near Lake Dobson inside the park. A hut situated close to your car has its advantages,

including the ability to cart in luxury items. A night of fine food – or in Jim’s

case a stale bread roll – plus fine wine and plenty of chocolate, has left us needing

some compensatory exercise.

Our morning weather

is clear, though rain is forecast later. That rules out the very long day trip

to Mt Field West, but also precludes a day sloughing about in the hut. After a

bit of pretend debate we choose what Tim and I already have in mind: the Tarn

Shelf/Newdegate Pass/Rodway Range circuit. And the highlight of

the walk, for us at least, will be the globally significant string bogs around

Newdegate Pass.

|

[Jim & Tim in the alpine zone, Mt Field National Park] |

But first we have

to traverse the familiar – and favourite – territory of Tarn Shelf. Pilgrims

of a different kind come here every autumn, as the tarn-dotted plateau has one

of the best accessible displays of deciduous fagus in Tasmania. We’ve been

among those pilgrims many times, but have also visited in every other season.

Jim and I chat about previous visits, some shared, some not. We eventually near

Lake Newdegate Hut, now in poor condition, and joke that both the hut and our

knees have seen better days.

But blustering about our “mature-age” fitness, Tim and

I con Jim into heading further up rather than turning around here. We plod up

the scrubby slope; totter over the boulder field; amble to the top of the

slope, and there we are: among the string bogs that dot the area around the

pass.

|

[Classic string bogs: looking west from Newdegate Pass] |

So what are

string bogs? Essentially they are interconnected micro lakes formed when peat and bolster heath plants (such as

cushion plants) impede the flow

of water in an already saturated landscape. When Mt Field National

Park was finally added to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area in 2013,

these string bogs were one of the reasons. They are quite uncommon not only in

Tasmania, but anywhere in the world.

Bogs they may be, but despond and despair are keeping

their distance. Not only do we stay dry-footed thanks to the excellent track

work here, but even when we venture off-track for photos and a good look, the

ground is far from “sloughy”. At an altitude of close to 1300m, and in a place

that was under snow only 6 weeks ago, that’s worth celebrating. So too is the

fact that the promised rain is still looking quite some way off.

|

[Looking towards K Col from Newdegate Pass] |

When such factors coincide, it’s worth dawdling. And

given our high level skills in that department, we find seven ways to go not-very-far-at-all,

starting with long photographic stops. Next we pause for a lengthy lunch among

some adjacent boulders, accompanied by the kind of jokey conversation we like

to pretend we’ve perfected by now. As we’re packing up lunch I mention that the

watery bogs we’re looking down at are technically known as flark ponds. The hilarity level rises and carries us loudly towards

our next destination: K Col.

By the time we’re scrambling up and around the Rodway

Range, however, joke levels have declined. It's hard work, and while none of us is exactly

despondent, Jim does start talking about it being wine o’clock. We know that,

in his case at least, whine o’clock

won’t be far behind.

|

[Jim & Tim on the Rodways, with Florentine and Tyenna Peaks behind] |

Still, there’s nothing for it but to keep walking.

Some comical videoing, a little mobile reception to call home, and a visit from

a pair of wedge-tailed eagles all do their bit to egg us onward. We

know there will be some tangible, edible rewards back at the hut. The

intangible rewards of our hours among those heavenly bogs may take longer to

work into our memories. But I suspect they'll be the longer lasting.

|

[Tangible rewards back at our hut] |

______________________________________________

*

Reflecting on where he lived, Winnie-the-Pooh’s friend Eeyore said: “It isn't as if there was anything very

wonderful about my little corner. Of course for people who like cold, wet, ugly

bits it is something rather special.”