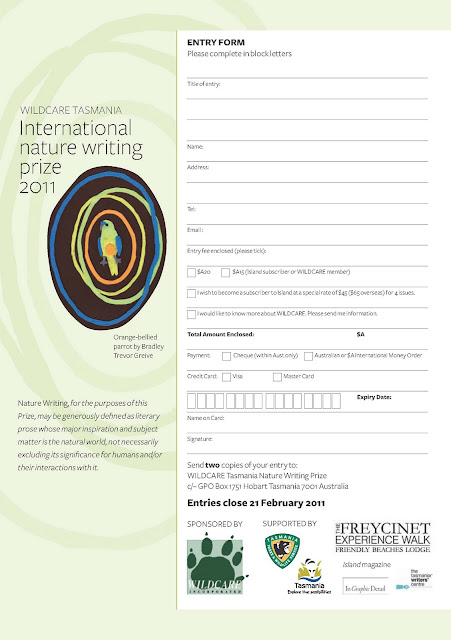

[My keynote address to the Interpretation Australia Symposium in Launceston, Tasmania - November 12, 2010]

|

[Curiosity, openness, wide-eyed wonder: characteristics of children - and of good interpreters. My grandson Felix models it here.]

|

Introduction

It is common to think of interpretation as layered. Many of us layer our interpretation to cater for different audiences. Some neatly categorise these audience types as streakers, strollers and studiers.

But have we considered that interpreters too are layered? Sometimes we stay on the surface and focus on what is plain to see. Sometimes we peel back the surface layers, and dig into difficult topics. And sometimes the interpretive process takes us very deep indeed; not only into our topic, but into our very selves.

It is this inner delving that forms the core of this paper. Using Tilden’s six principles of interpretation as a starting point, we ask whether it’s time to develop some new principles. Can we advance a set of principles that address the personal formation of interpreters?

We put forward some suggestions for this inward journey. We consider how these might affect the place of the interpreter in the interpretive process. And we put a question that is both idea and a challenge. If we interpreters are committed enough to our subject to go deep within ourselves, might we paradoxically end up presenting that subject to its greatest advantage?

Finding what cuts through

I live near the Hobart Rivulet. It is a narrow, brief, rushing thing, literally cobbled together from dolerite boulders torn off the crumbling flanks of Kunanyi/Mt Wellington. Steep-banked, scrubby-sided, pocked and youthful, it is a duckling with few prospects of a serene swanhood. But every so often – perhaps every other year – the rivulet asserts itself, and floods so profoundly that boulders the size of lounge chairs are tossed and tumbled by the force of water.

One such episode occurred in early August this year. The rolling boulders could be heard – or felt – from inside our house, some 100 metres away. We were inside the house, the rain thumping heavily on our corrugated iron roof clashing with the roar of the water and the loud music coming from our sound system. Yet above – or beneath – it all was a deep, visceral, almost animal thrum. The sound of boulders grinding, tearing, bouncing so vigorously that the ground shook.

|

| [Hobart Rivulet in South Hobart in a quieter mood] |

What is it in your life that thrums so deeply that it can cut through all the other things that clutter your life? Theologian Paul Tillich spoke about “the ground of our being” – what he called God. Whatever we call it, I believe most of us have that growl, that rumble – for some subliminally – that can cut through everything else; make all else seem trivial. It is worth finding the source of that thrum; worth cultivating it, and worth growing our souls in the process.

Revisiting Tilden

Such an approach actually arises straight out of Interpretation 101, that is the basics of interpretation as outlined by Freeman Tilden more than half a century ago in his book “Interpreting Our Heritage”.

In this 1957 work Tilden comes up with Six Principles. As if anticipating a generation or more of queries about the number and nature of the principles, he asks: “Now, what are these principles? I find six bases that seem enough to support our structure. There is no magic in the number six. It may be that my reader will point out that some of these principles interfinger.” Or, he continues, “since I am ploughing a virgin field so far as published philosophy of the subject is concerned, some of my readers may be provoked into adding further furrows.”

Tilden deliberately focuses the principles on what he calls the interpretive effort. But interestingly he also mentions the matter of style, which he calls a “priceless ingredient of interpretation”. Style, he says, “is just the interpreter himself.” He goes on to ask how the interpreter might give forth style, answering his own question thus: “It emerges from love.”

Was this wise elder deliberately leaving open a door to the re-interpretation of interpretation by his mention of style and “the interpreter himself”? And through his metaphor about adding “further furrows” to the field? In the early 21st century, where technique and technology are merging, and threatening to dominate the interpretive effort, I am willing to argue that he was. To me it seems the right time to turn the focus back onto the inner life – the personal formation – of the interpreter.

To do this I have attempted to re-mix Tilden’s principles with the inner life of the interpreter in mind. I hope I’ve done this with the greatest respect for Tilden who, as Sam Ham puts it, was so far ahead of his time that he could fairly be called the Einstein of interpretation.

My own humble effort is necessarily brief and tentative, with more questions than answers. But hopefully it will plough some furrows which others may follow, or into which they might sow.

Tilden’s Six Principles of Interpretation re-mixed

Principle 1) Any interpretation that does not somehow relate what is being displayed or described to something within the personality or experience of the visitor will be sterile.

Re-mixed : “Any interpretation that does not somehow relate what is being displayed or described to something within the personality or experience of the interpreter will be sterile.”

This is the starting point for using Tilden to explore the inward journey: the personality/experience of the interpreter. Interpretation may be an outward, audience-focused work, but in a very real sense every piece of interpretation starts within the interpreter.

There at the start of the interpretive piece we have the subject/object and we have the interpreter. And the interpreter needs to relate to that subject/object in some manner, even if it is with disdain! Otherwise a rote recital or a robot will do fine; or interpretation as a paint-by-number exercise will suffice.

So how do we learn to relate to our subjects? The poet Les Murray once said “I am only interested in everything.” We can develop an interest in many things if we cultivate an intellectual curiosity; if we read widely; if we listen to others; if we realise we don’t have all the answers; if we understand what an incredible gift life is, and how rare it is in the universe; if we not only observe life, but actually live it.

In having our personality as a focus, I am NOT suggesting that we interpreters need to necessarily have our personalities out there on show. But they should be in there and relating to our subject (and of course to our audience).

Principle 2) Information, as such, is not interpretation. Interpretation is revelation based upon information. But they are entirely different things. However, all interpretation includes information.

Re-mixed: “Interpretation is not just about information, but about revelation. The interpreter must be open to revelation.”

Revelation to the audience presupposes revelation first to the interpreter. And nothing is revealed to those who aren’t looking. So again an attitude of openness is required of the interpreter. We have already touched on intellectual curiosity. To that I would add developing intelligence per se. Tertiary study is one way, but there are many others, including specialist study; careful research; wide reading; subscription to journals and good old fashioned asking questions.

Let’s seek to stay both open-minded and intellectually lithe as we grow older. Let’s resist succumbing to forces and habits that entrench and ossify our thinking. Being open to revelation, open to being shown new things, or perhaps old things in new ways, also means that we will resist fundamentalism of any sort. A closed mind will not be open to new thinking. Have an opinion; know what you believe; defend your position by all means. But remain open-minded, including to the possibility of your own biases, prejudices and fallibilities. Above all, remain open to what your life has to show you.

A willingness to sometimes be quiet and still seem important to this. In the 1940s E.H. Burgmann, Anglican Bishop of Canberra/Goulburn, reflected on the special places of his Australian bush upbringing, and the place of humans in the natural world.

“It is foolish for man to think of Nature as below him. If he lives in the bush long enough he will find that reverence is the only worthy attitude. But the bush will take its own time to do the work. It will not speak to a man in a hurry. Its message is worth waiting for. Only the soul that is stilled in its presence can hear the music of its song."

If Bishop Burgmann is right, learning from nature – and from the wider universe – may take a great deal of patience; a willingness to listen; a capacity to be still. Such openness is a kind of spiritual labour.

Principle 3) Interpretation is an art, which combines many arts, whether the materials presented are scientific, historical or architectural. Any art is in some degree teachable.

Re-mixed: “Interpretation is in part an art. The interpreter needs to consider how to be/become artful.”

As well as cultivating a broad intellect, this principle asks that we cultivate art within ourselves. I see art as an attempt to give shape to the shapeless. Be it via visual arts, music, literature, movement or performance, art at its best explores big questions; questions about meaning, love, justice, and some things that we struggle to otherwise articulate.

Have you ever stood in front of Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles at the National Gallery? Or any of Giacometti’s extraordinary sculptures? I know little of the questions asked, or the answers given by those works, and yet somehow my life is the richer for having seen them.

Consider now some of the art or music or poetry or performance that has moved you. Perhaps it is this power to move us that makes art so important. As interpreters are we still open to being moved? Are we still teachable? Or do we tend to be “know-it-alls”?

Let’s determine to remain wide-eyed and open-minded; in touch with our emotions, and self-confident enough to be moved. Because life, in all of its triumph and tragedy; its banality, joy and pathos, is an extraordinary phenomenon that ought to move us. If we are unmoved by life, if we allow a carapace of casual cynicism, a shield of self-protective fear or a façade of fascinating facts to protect us from being moved, then both we and our interpretive audiences will be the poorer.

|

| [Power, silence, green peace: The Mersey River cuts through forest near Tasmania's Overland Track] |

As well as simply experiencing art, I believe it’s important to explore and cultivate our own artistic, creative side. Whether or not this is incorporated into our interpretation is irrelevant. Every single one of us has a creative side that is wanting to be expressed, even if it’s only for ourselves or our most tolerant family and friends. What art do you, or might you practice?

Principle 4) The chief aim of Interpretation is not instruction, but provocation.

Re-mixed: “The chief aim in the inner formation of an interpreter is not just to be instructed, or to learn, but to provoke ourselves.”

If we are to provoke our audience, we can start by provoking ourselves. The literal meaning of provoke, coming from the Latin provocare, is “to call forth”. Tilden is following and quoting Ralph Waldo Emerson, who said that “it is not instruction but provocation that I can receive from another soul.”

Again we are talking about the things that are already there inside each one of us. The re-mixed principle asks us to “call forth”, to give expression to, to be moved by those things that matter to us.

What is it inside of you that needs to come out? I’m not speaking here about those fault lines in your personality that might best be poured out to a therapist or a confessor, as important as that may be. Rather I’m speaking of such things as your love of history; your passion for place; your anger at destructive practices; your amazement at a natural phenomenon; even your desire to connect with an audience and see the light bulb flickering on above their heads.

We can have all the knowledge there is to have about our subject, but if we haven’t been provoked in some way concerning our thoughts and feelings about that subject, then why are we trying to interpret it? We might as well be a robot.

Finding out what it is that needs to be called out of you will require reflection. This can be individual and private, but it might also come out through group work or significant relationships with others. Self-help is rarely the sole answer here, so it will be helpful to seek out others who are willing to explore these issues with you.

Principle 5) Interpretation should aim to present the whole rather than a part, and must address itself to the whole person rather than any phase.

Re-mixed: “In presenting to the whole person, the interpreter needs to strive to be a whole person themselves.”

All of the principles seem to lead to this one point. For how can people who aren’t personally striving to be whole aim to present the whole.

It’s not that the interpreter is some kind of perfect being, a Renaissance “man” who simultaneously rides a horse while shooting a bow and arrow, composing a love sonnet and playing a lute. Rather we ask ourselves “what is the whole; how can I be whole”? We seek for ways to integrate everything in our lives; to bring things together rather than to dissect and scatter.

Earlier I talked about true openness being a kind of spiritual labour. I used the word spiritual advisedly, because I think that part of the thrum that registers in most of our lives – more for some than for others – has to do with spirit, with soul, with the transcendent, with the mysteries that we grope towards but don’t often know with certainty.

We can approach the transcendent in many ways, and from many traditions. Prayer, music, art, meditation, poetry, worship, literature: these are some of the tools we might use. If we are to strive towards being whole people, it’s my contention that we need to find some way of approaching the transcendent.

And we need to find a language in which we can share such strivings. Australians have not always been good at articulating their spiritual or internal struggles. If we can’t easily raise such things in the average morning tea room, then at least we might try to find people with whom we can share such things. Because another truth about wholeness is that it is a corporate and not just an individual matter. We are not whole as a person if we are not in some kind of human community.

Principle 6) Interpretation addressed to children (say, up to the age of twelve) should not be a dilution of the presentation to adults, but should follow a fundamentally different approach. To be at its best it will require a separate program.

Re-mixed: “Interpreters presenting to children follow a fundamentally different approach. In so doing they are also recognising the value of childlike characteristics for the interpreter.”

I think it would be fair to say that, as important as this principle was to Tilden, it appeared at first to be something of an afterthought. And yet … few things that look casual or throw-away in Tilden turn out to be so. Time again we find that he knew – or intuited – what later study would bear out. So here, we find him early among those who recognised the importance of reaching children through interpretation, and doing so in an age-appropriate manner.

In recognising both the importance of, and the different nature of children, we are acknowledging the importance of child-likeness. Think of characteristics we often associate with children: playfulness; curiosity; naivety; a capacity to keep asking questions; a sense of fun; a wide-eyed sense of wonder; the ready expression of emotions; a willingness to depend on others; a capacity to acknowledge ignorance … the list could go on.

Aren’t these some of the characteristics that we interpreters would want to be cultivating in ourselves? As an interpretation manager I would be more than happy to see some of them re-mixed into an interpreter’s statement of duties!

To sum up this attempt to find principles for the interpreter’s inner journey, I would like to bring together two golden threads: one from Tilden, the other from Blind Willie Johnson. The former, as we have already seen, believed that the defining ingredient for the interpreter was love. The latter, in his Depression era blues classic, asked “what is the soul of a man?” Blind Willie Johnson’s guileless answer was “it ain’t nothin’ but a burnin’ light”.

Our life, our light, isn’t going to burn forever, at least not here on earth. But while it burns, fuel it with love and shine it on things that matter.