Grounded: (adjective) sensible and down-to-earth; having

one's feet on the ground; (verb) to confine (a child) to the house as a

punishment. (Collins Dictionary)

For the

past 6 weeks I’ve been grounded. In the aftermath of our Mt Anne “epic”, and the

ankle injury I sustained there, I’ve had to be very sensible about how I put my

feet on the ground. And it has involved enough confinement to make it feel like

a punishment.

|

[Let me outa here! I need to walk!] |

The backstory

can be found here Mt Anne Epic Part 2. But to put it simply, politely, I badly sprained my ankle. According to the

physiotherapist I probably tore my soleus muscle. This lurks somewhere beneath

the Achilles tendon, near quite a few other equally unpronounceable bits and

bobs. And I didn’t confine the damage to that muscle. The harm from the initial

twist spread to quite a few other unnamed parts, thanks to the steep, rough and

hot 10 hour hobble back to the car. It all hurt, and I could barely walk for

two days after getting home.

So while

the summer variously sizzles and fizzles itself out, I’ve been slowly recuperating.

It has involved more “thou shalt nots” than “thou shalts”. I can do

some simple (and boring) physio exercises and I can wear an ankle support

brace. But I can’t run, and I can’t walk anywhere too rough. Nor can I walk very far or carry much weight on my back. And that has meant no overnight bushwalks

since early January.

So what

does a passionate walker do, at the height of the walking season, when that activity is curtailed? For a start I dream of

walking. I pore over maps, plotting and planning walks that I WILL DO when … I also walk

vicariously, listening to friends talking about their trips, reading others’

accounts of their walks.

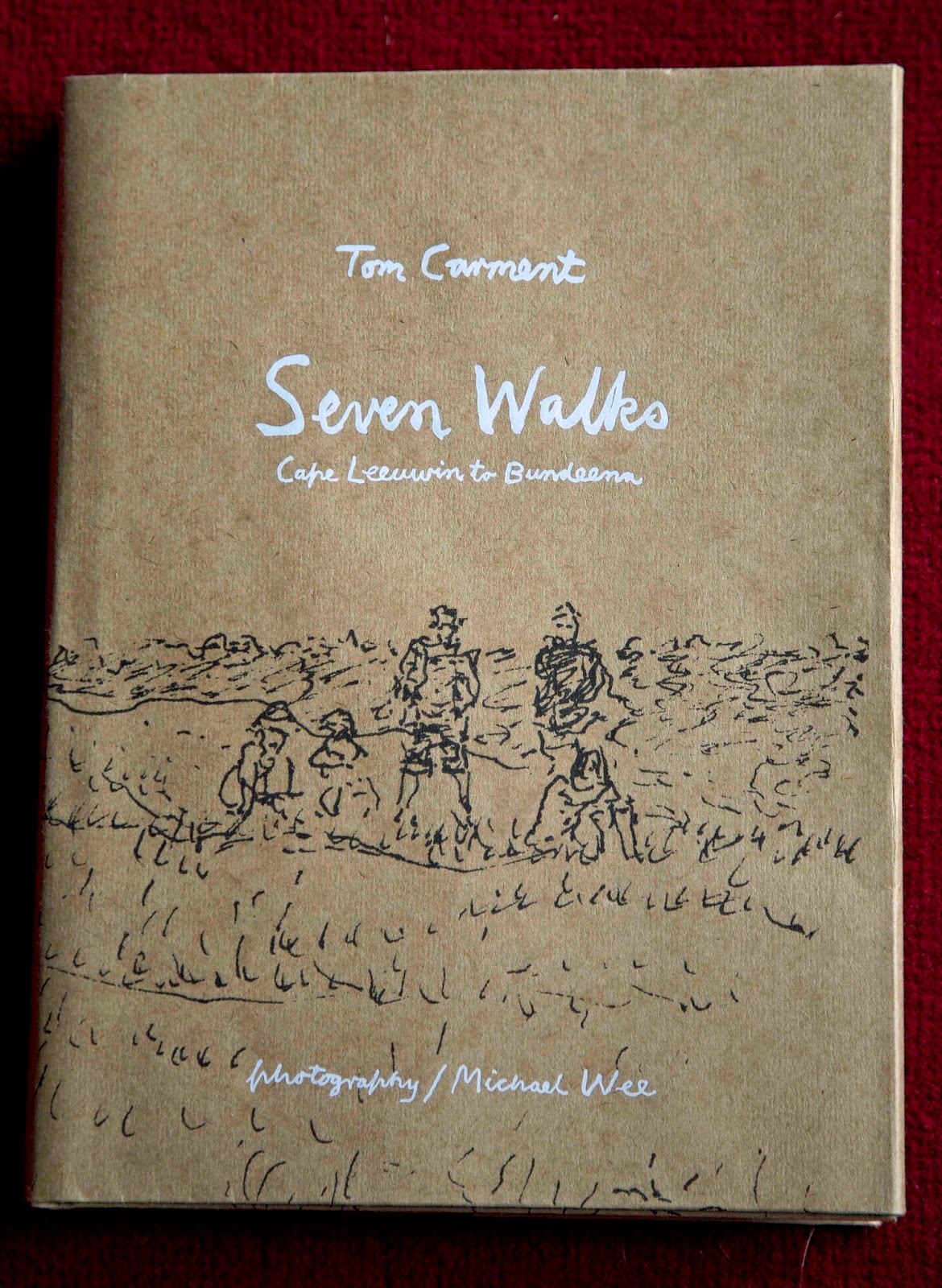

My

dreamwalking is always being fed by books. But during my recent confinement, Tom Carment and Michael Wee’s “Seven

Walks: Cape Leeuwin To Bundeena” has happily filled a void. As well as its beautiful and artful

presentation, I am enjoying its spare, wry observations about bushwalking in

Australia. I laughed, for instance, at Carment likening the randomly gathered walkers

on the Overland Track to “the cast of their own six-day play.”

English

poet Simon Armitage’s “Walking Home” is a delightful take on the long distance

Pennine Way. Armitage walks from the Scottish border to his Yorkshire home, giving

poetry readings each evening in return for his bed and board. It’s probably

only the English weather that creates any semblance of adventure here. But this

book is more about the characters and places Armitage meets along the way than it is about the walk itself.

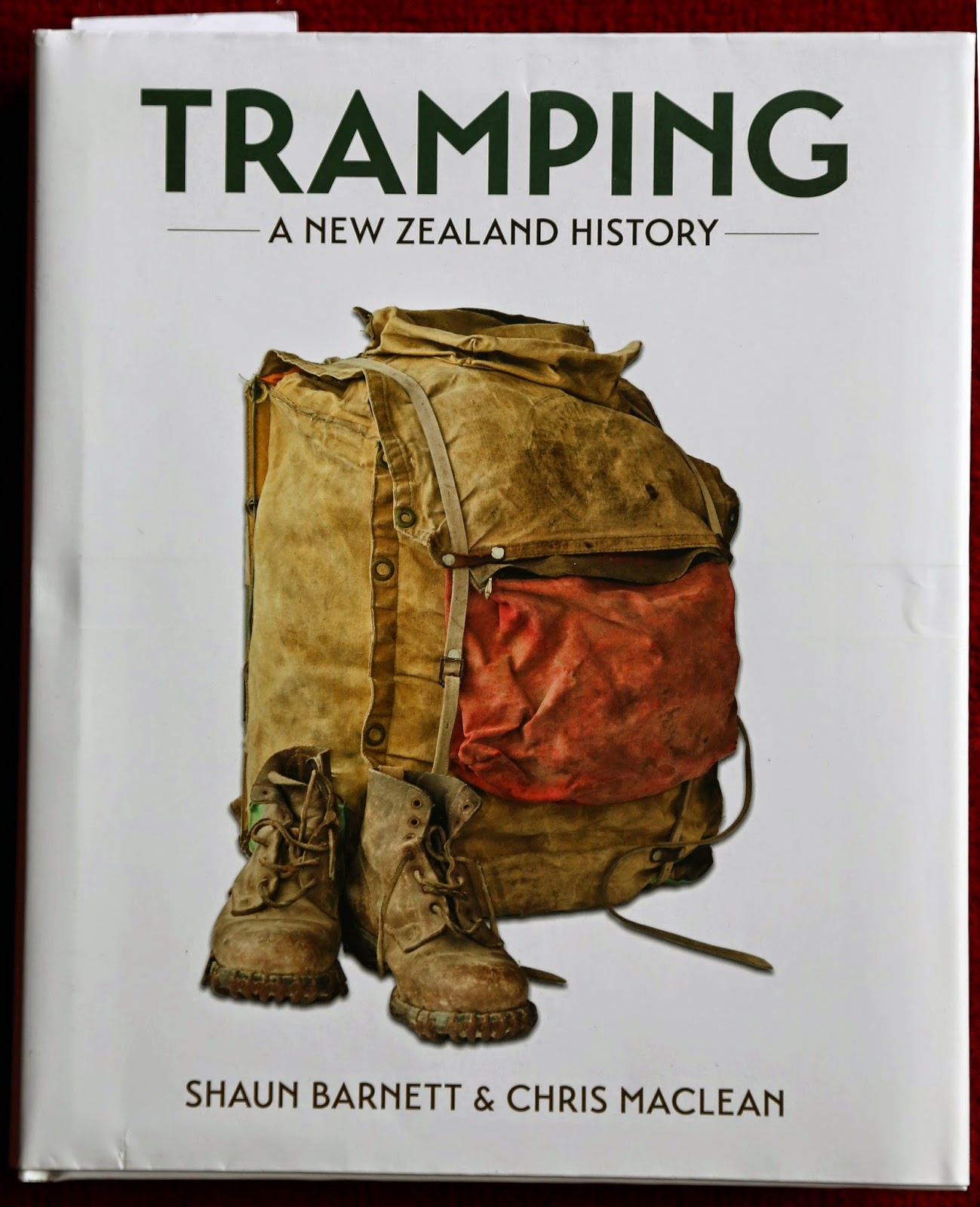

“Tramping:

A New Zealand History” by Shaun Barnett and Chris Maclean is a monumental – and

beautifully illustrated – account of tramping in New Zealand. This is a book to

dip into endlessly, whether to learn the origins of the word “tramp”; to hear

of the unique place of huts in NZ walking; or to admire the feats of pioneers

crossing the Southern Alps. I managed to bring the book back from New Zealand

late last year as “hand luggage”. If you want to try the same, I’d suggest you

do some arm strengthening exercises. This wonderful book weighs in at almost

2kg!

Despite

this wealth of indirect experience, I've concluded that it’s only actual walking that

is properly good for your body and soul. So last weekend I donned my boots – and my ankle

brace - and fought off my growing cabin fever via an exploratory walk on the mountain.

It involved some steep, rough slopes (don’t tell my physio!), but the reward was

the discovery of two mountain huts I’d never been to. I survived the walk well enough to imagine that my next book just might be a bushwalker's log book!