We travel, in essence, to become young fools again - to slow time down and get taken in, and fall in love once more. – Pico Iyer

I had wondered: would last year’s long

journey on foot, 2 weeks and 250km across Portugal and Spain, sate my love for journeying? The answer came swiftly when I was offered the chance to join a

small group riding 380km across my own island state of Tasmania. Of course I

would go.

|

[Riders heading towards Tasmania's East Coast] |

The excuse, if any was needed, was provided

by an electric vehicles conference being held in Devonport. The organisers

thought an apt prelude to the conference would be an e-bike ride from Hobart to

Devonport. Lynne and I had recently purchased e-bikes, and our friend Tim had

soon followed suit. And it was Tim who invited us both to come on the ride.

That sometimes ugly four-letter word – work – precluded Lynne from coming. But

I agreed to join Tim, and we soon commenced rigorous training. Actually we just

did a couple of relatively short rides, more to acquaint ourselves with our

bikes’ abilities than to tone any cycling muscles.

|

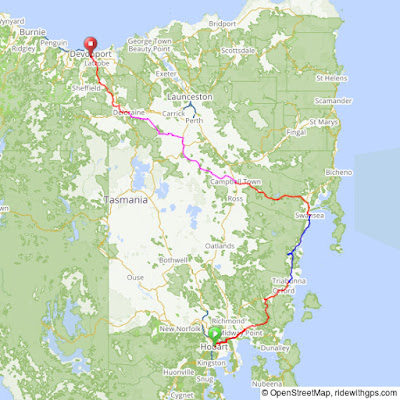

[Our planned route from Hobart to Devonport] |

For those not familiar with the workings of

e-bikes, it’s important to say that they are definitely NOT motor bikes. While

they vary one from another, most e-bikes have a small battery-powered motor

that is only activated when you pedal

(variously called pedelec or pedal-assist). To get anywhere you still

have to pedal, and sweat, and occasionally strain. That said, there’s a fair

chance that you’ll do so with a smile on your face.

|

[Riders ready to leave Hobart] |

Our chief organiser, Jack, has arranged a

public send-off from Mawson Place in Hobart. On a showery, cool and windy spring

day, watched by a small entourage of supporters and media, we are sent on our

way by Hobart’s Lord Mayor, Sue Hickey. With a degree of panache, she chooses to snip the ribbon with scissors while riding

her own electric tricycle, as though she’s never been cautioned about running

with scissors.

|

[Mayor Sue Hickey on her e-trike about to send us off] |

Here the fields may be starting to fill with

warehouses – and real houses – but the sky is wide and it feels as though the

ride has really begun. Instead of contending with traffic, we take on the

weather, which is blustery and showery, especially crossing the causeways to

Midway Point and Sorell. At the latter we stop for two of the

practicalities that will become our constants: topping up our batteries and having

morning coffee.

|

["Spaghetti Junction" at the Sorell recharging] |

We then take a winding gravel road between Sorell and Buckland

via Nugent. This is often a drier part of Tasmania, but this spring it is green and

pleasant, the fields close to lush, the forested hills blushing with fresh

growth. It’s not hard to love our island given the chance to see, smell and

hear it so intimately. And we’re more relaxed on the quieter route, sometimes travelling

two or three abreast, and getting to know each other in the process.

|

[A rest stop on the Nugent Road] |

But the Nugent Road ride also tests us, as we have

to climb to more than 300m before the descent to Buckland. The good news is we

have a tail wind to add to our motors, and that makes the hills more manageable.

The bad news is that the showers are increasing, and occasionally we’re getting

hammered by hail. The convoy spreads out and sociable chatter declines. Now we’re Brown’s

cows more than a peloton.

Near the top Tim, in his campervan/support

vehicle, decides to pull over and boil up a fortifying brew. Refreshed and

regrouped, we set off for the mostly downhill run to our lunch/recharge at the

Buckland Roadhouse. Gravity and hunger get us there, and after our hard riding,

we have no qualms about devouring plenty of hot, high-fat food.

But I do have conscience on another front, and invite Tim to have a ride after lunch, while I take a turn driving the campervan. It proves an inadvertently shrewd move on my part, as the weather deteriorates further on the afternoon run into Triabunna. Showers turn to rain, and Tim and co. get a good soaking before the convoy turns off into the Triabunna Caravan Park. Still it’s been a good 85km ride, and even if we’re wet, we can be pleased with our day 1 achievements. Once we’re dry and fed, we’ll sleep the sleep of the righteous.

.jpg)